Exchequer receipt roll: Monthly and Weekly Trends

In the last post (Exchequer receipt roll: Overview of Payments) I showed an overview of the payments in the 1301/2 receipt roll of the Irish Exchequer. This prompted a question from Dr Richard Cassidy:

Interesting analysis. Was income concentrated in the first week or two of the Michaelmas and Easter terms, from the sheriffs’ adventus, as in the English receipt rolls from the 1250s and 60s?

— Richard Cassidy (@rjcassidy) March 20, 2020

The adventus refers to the Adventus Vicecomitum or the ‘appearance of the sheriffs’, where sheriffs would appear at the English Exchequer twice a year to pay in money they had collected for the king. [1]

In this post, we’ll first break-down the returns on a monthly, then weekly basis, which will help answer Dr Cassidy’s query.

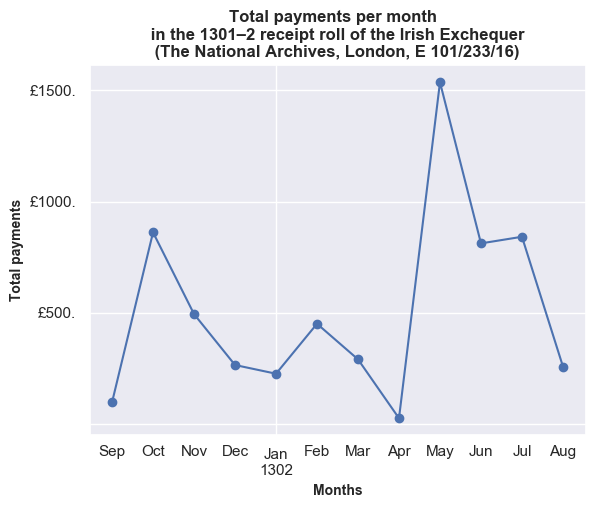

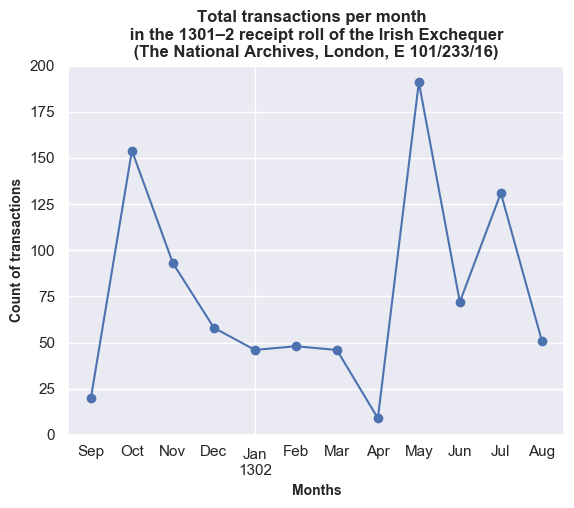

In the following two plots, we can see the monthly distribution of income coming in and how many individual transactions. The peaks and troughs seem to follow a similar pattern between the amount of business before the exchequer and the amount of revenue, i.e. the totals aren’t dominated by a small number of high-value receipts.

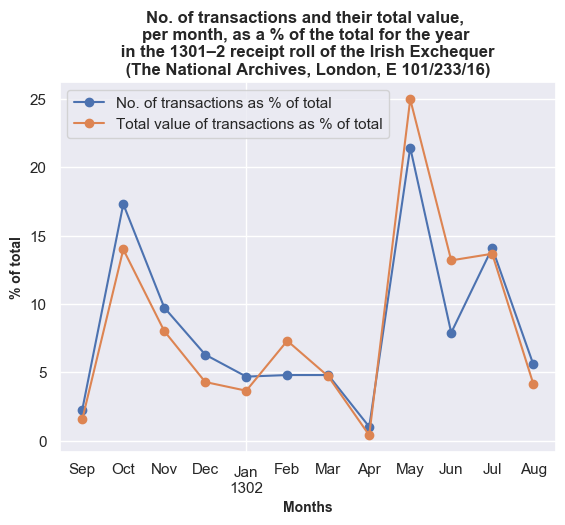

This can be seen more clearly in the following plot where the data is normalised by showing the total value of receipts and the total number of transactions as a percentage of the totals for the whole year.

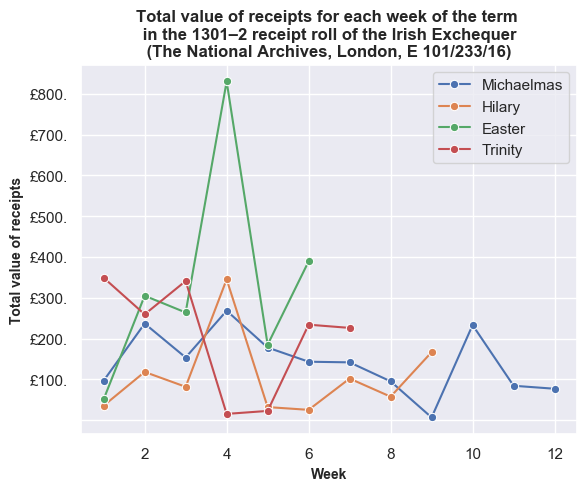

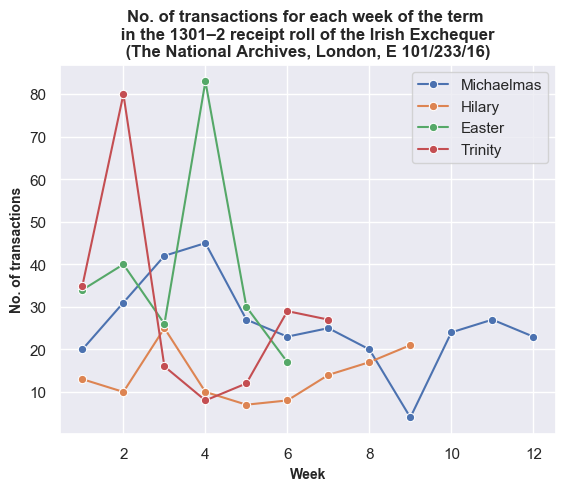

How does the picture look if we break-down the Exchequer business onto a weekly basis? The following two plots show the total value of receipts and the number of transactions for each term. The line plots are a little jarring since the financial terms are not of equal length. It should also be noted that I take a week as business occurring from Monday to Saturday. Thus, not all weeks will have the same number of days, depending on when they start and end. For example, the first week of Michaelmas only represents one day, since the term began on a Saturday. Also, some weeks exchequer didn’t sit due to feast days.

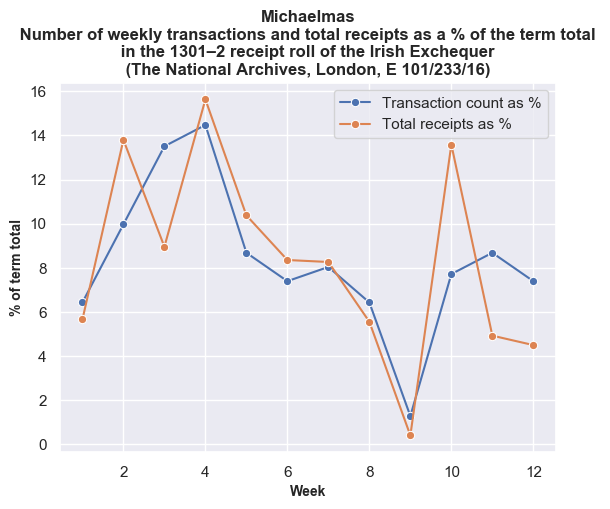

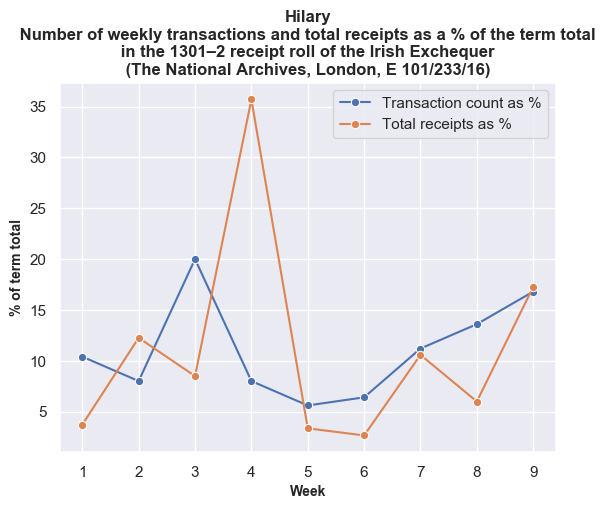

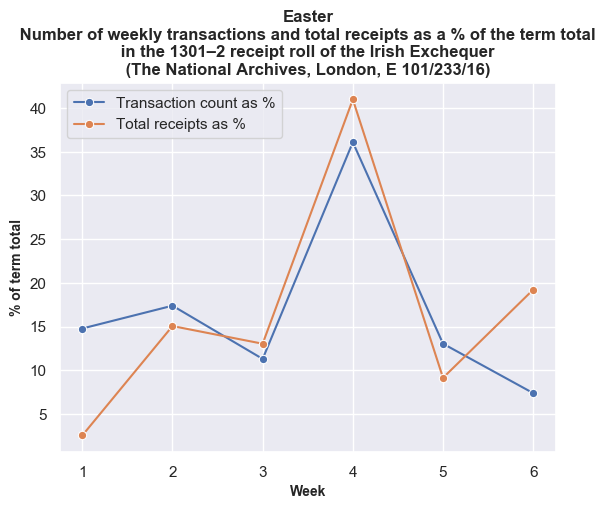

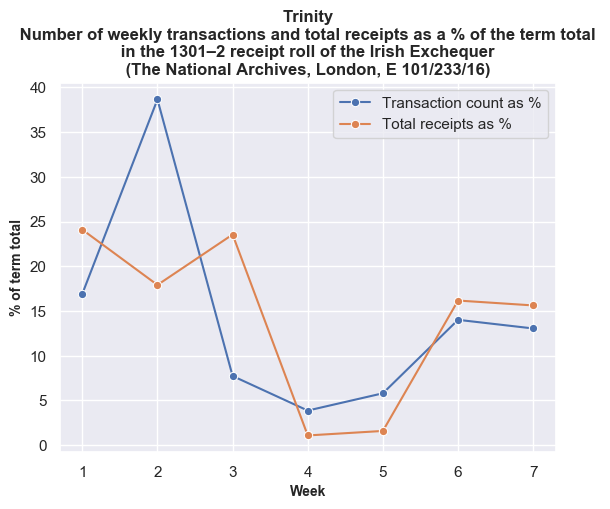

The trends are more evident if we look at each financial term individually. Here the data is normalised by showing the total value of receipts and the total number of transactions as a percentage of the totals for each financial term.

Once again, the weekly break-down generally shows a similar pattern between transactions and values with some exceptions on certain weeks. For example, in the tenth week of Michaelmas, the spike in payments against a lower number of transactions is accounted for by Roger Bagot, sheriff of Limerick, returning £76.6s.8d. for the ‘debts of divers persons’; and £100 being returned by William de Cauntone, sheriff of Cork, in forfeited property of felons and fugitives. In Hilary, the higher spike of values against a low number of transactions occurs due to a small amount of high-value payments from Cork on 5–6 February 1302, including £99.13s.7d. for the farm of the city, and a further £173.6s.8d. in aid promised to the king. The spike in payments received in the third week of Trinity is caused by a substantial sum of £310 proffered by Thorosanus Donati, attorney of the merchants of the society of Frescobaldi. Whereas, the high number of transactions compared to the lower total values in the second week is caused by that week having a high number of receipts (80), of which around 45% were valued at a pound or less.

So, returning to Dr. Cassidy’s question: ‘was income concentrated in the first week or two of the Michaelmas and Easter terms, from the sheriffs’ adventus, as in the English receipt rolls from the 1250s and 60s?’

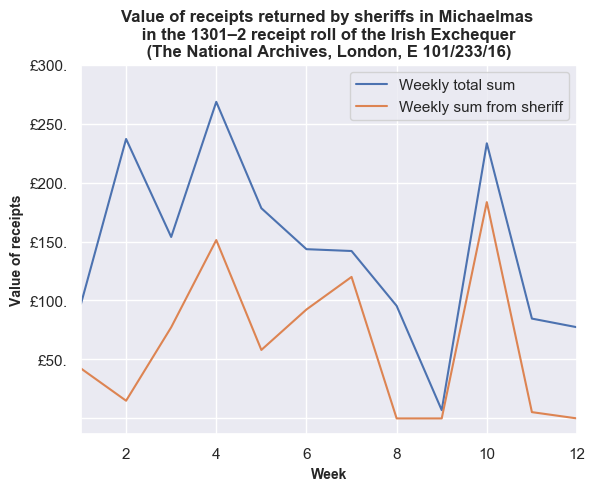

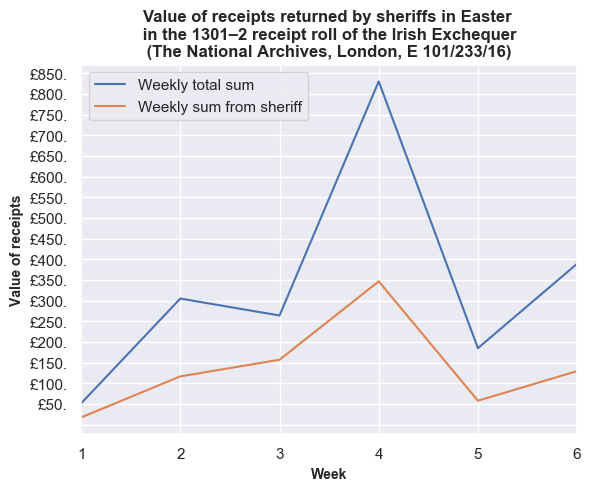

We can see that the bulk of the income for 1301/2 came in October (Michaelmas) and May (Easter). However, in both terms, most of this was accounted for in the fourth week, and not the first two. Did the sheriffs account for the bulk of these payments? By querying the dataset, we can pull out amounts that refer to sheriffs in the Michaelmas and Easter terms, and plot those values against the total weekly sums.

Warning: in a couple of places, the value returned by the sheriffs will be under-represented slightly. Generally, if a sheriff is entered in two or more consecutive rows, the first row gives the name, e.g. ‘John Wodelok, sheriff’. The following and subsequent entries state ‘the same sheriff’. However, on at least two occasions, the next entry just declares ‘the same’, and these are not recognised as a sheriff in our current query. This should be rectified with future improvements in our entity recognition, and the occurrences are so few for sheriffs to have a minor effect on accuracy.

For Michaelmas, sheriffs accounted for just under half of the values returned in the fourth week, but most of the total on the tenth week. Again, in the Easter term, sheriffs accounted just under half of the total amount returned.

So, the initial analysis would indicate both similar and different practices in Ireland during the reign of Edward I, compared to England under his father, Henry III. The spikes in Michaelmas and Easter suggest that the Crown expected a proffering at the Irish Exchequer, but the timings of the payment differed. The later payments in the Easter financial term might be explained by the timing of the feast of Easter, which was 22 April in 1302. However, a note of caution is needed. This is only a snapshot of a single financial year. Does this pattern reflect other years? Does practice shift over time? Is there a difference in recording, i.e. is the sheriff bringing money to the Irish Exchequer, but another person or institution is recorded in the receipt roll as answering for the rent, debt or fine?

[1] R. Cassidy, ‘Adventus Vicecomitum and the Financial Crisis of Henry III’s Reign, 1250-1272’, The English Historical Review, Vol. 126, No. 520 (June 2011), 614-627 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/41238716.